‘The labor movement must be crushed!’

By BERRY CRAIG

AFT Local 9005

In the late 19th century, the American labor movement united behind the eight-hour workday.

The American Federation of Labor called for a nationwide strike for the eight-hour-day on May 1, 1886. Thousands of workers walked off their jobs in dozens of cities, including Chicago, a union stronghold.

Meanwhile, union-despising Cyrus McCormick, owner of Chicago’s big McCormick Harvester Co. had locked out workers who wanted a union and brought in strikebreakers. On May 3, when the workers and their sympathizers confronted the scabs, the Chicago police—notoriously anti-union--rushed in. They opened fire on the workers and their supporters, killing four and wounded several more.

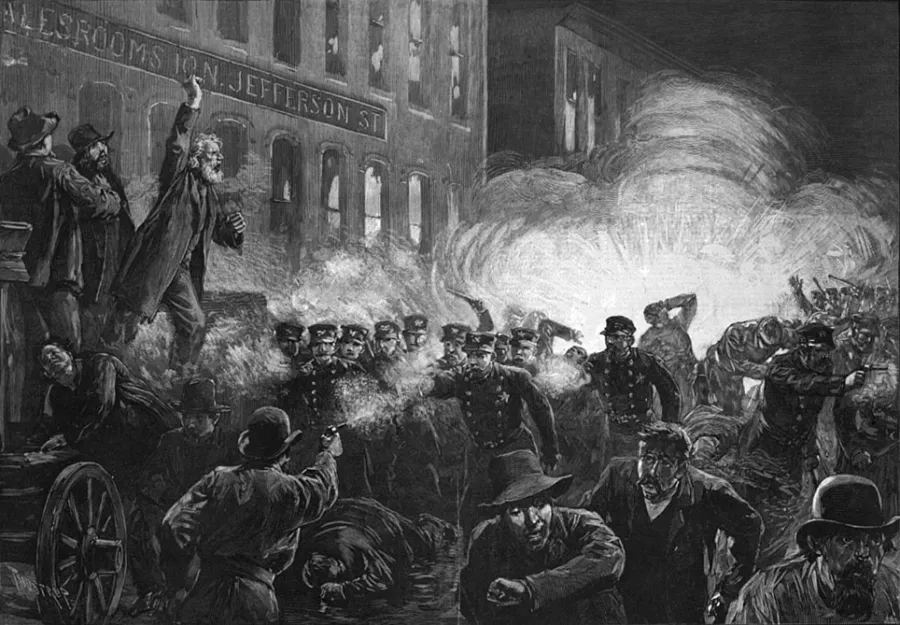

Radical unionists called Anarchists sponsored a protest rally at Chicago's Haymarket Square on May 4. An estimated 3,000 people came and listened to speeches denouncing police brutality.

The protest--peaceful by all accounts--went on well past sundown. Around 10 p.m. the rally was winding down. Many in the crowd had left; it was starting to rain.

"A detachment of 180 policemen showed up, advanced on the speakers’ platform, ordered the crowd to disperse," historian Howard Zinn wrote in A People's History of the United States. "The speaker said the meeting was almost over."

Added Zinn: " A bomb then exploded in the midst of the police, wounding sixty-six policemen, of whom seven later died. The police fired into the crowd, killing several people, wounding two hundred."

Who threw the bomb? To this day, nobody knows.

Egged on by Chicago’s wealthy powers that be and by the city’s fiercely anti-labor and anti-immigrant press, the police rounded up eight anarchists, most of them German-born. “Justice should be prompt in dealing with the arrested anarchists," the Chicago Journal demanded. "The law regarding accessories to crime in this State is so plain that their trials will be short.”

There wasn’t a shred of evidence linking any of the accused to the bomb. Six of them weren’t even at the square. But they all faced the same trumped up charge: conspiracy to commit murder, same as murder, a capital crime.

The press clamored for eight executions. Papers shrieked—without a scintilla of proof--that the bomb blast was part of a gigantic conspiracy hatched by labor radicals—especially foreigners--to overthrow the U.S. government.

Members of the jury were business owners or their employees. They were hand-picked for their anti-union and anti-immigrant bias. One was related to a dead policeman. He freely admitted that he was prejudiced against the defendants.

The police threatened witnesses with torture unless they lied. Other were paid off to lie.

The judge was notoriously anti-union and anti-immigrant. In his charge to the jury, he all but told the 12 men to hand down a guilty verdict. They didn’t disappoint him.

In one of the worst miscarriages of justice in U.S. history, all eight were found guilty; all but one was sentenced to hang. He got 15 years.

As defense lawyers appealed the verdict, protests erupted nationwide and around the world.

Though the trial was an obvious farce, Gov. Richard Oglesby, a Republican, was attuned to the anti-union and anti-immigrant sentiment in his state. So he refused to pardon the men, though he commuted two of the death sentences to life in prison.

Another cheated the hangman by killing himself. The other four were hanged in 1887, leaving two more awaiting execution.

In 1893, Illinois Governor John Peter Altgeld, a liberal Democrat, denounced the trial and pardoned the remaining two condemned men--and the man who was sentenced to 15 years--and denounced the trial. Savaged by the press and the Republican Party, he was not reelected.

In the wake of Haymarket, the anti-union press and anti-union politicians claimed everybody who was in a union was a potentially dangerous radical out to destroy the county. Because they were the country’s largest labor organization, the Knights of Labor was singled out for attack.

The new AFL, an association of skilled labor unions, survived but only by concentrating on winning better pay, hours and working conditions for its members, not the broad-based reform that the Knights sought.

"No, I don't consider these people to be guilty of any offense, but they must be hanged," a Chicago businessman said of the eight anarchists. "I'm not afraid of anarchy; oh, no, it's the Utopian scheme of a few philanthropic cranks, who are amiable withal, but I do consider the labor movement must be crushed! The Knights of Labor will never dare to create discontent again, if these men are hanged!"