Grupper's remarks at the Global Studies Association/Global Studies Conference at Howard University

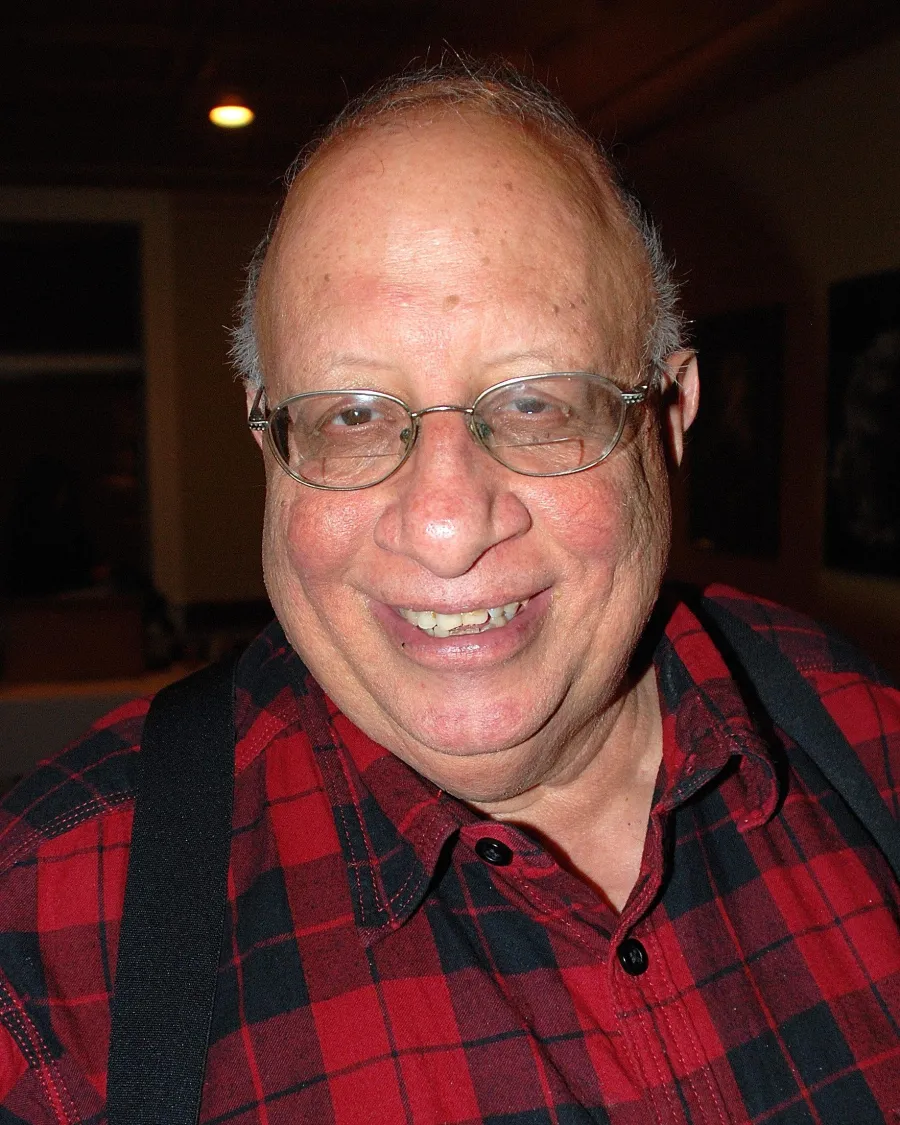

EDITOR'S NOTE: Grupper is a veteran Louisville civil rights and labor activist.

THE LEGACY OF THE SOUTHERN CIVIL RIGHTS MOVEMENT

By IRA GRUPPER iragrupper@gmail.com

(Note: I am grateful to several Civil Rights Movement colleagues for reading a draft of this paper and suggesting changes. Jodey Bateman’s input has been incorporated into text—without proper attribution! Any errors or lack of clarity are mine alone. I.G.)

The dictionary defines “legacy” as something transmitted by or received from an ancestor or predecessor or from the past: the legacy of the ancient philosophers; the war left a legacy of pain and suffering.

To understand the legacy of the Civil Rights Movement, one must look at the material conditions that gave rise to it. Chattel slavery was a crime against humanity, but this paper has no way to cover it.

We will start with its offspring: racial segregation. Racial segregation was an abomination. There were few possibilities for legal redress.

But there were some. When the US Supreme Court ruled against segregated schools (“separate-but-equal”) in Brown v. Board of Education in 1954—racist resistance became a tidal wave.

In the late 1950’s President Eisenhower, a Republican, would not send in troops to Little Rock, Arkansas to protect students integrating a white high school—until the possibility of racists murdering these students wholesale was on the horizon. Only then did he send in troops and federalize the Arkansas National Guard.

President Kennedy, a Democrat, would not send in troops to protect James Meredith while he was becoming the first African American to integrate the University of Mississippi. It was only after two people were murdered that he ordered in troops.

Gov. Ross Barnett of MS had stated: “No school in MS will be integrated while I am your governor”.

The U.S. House of Representatives and the U.S. Senate were racist-infested. Most standing committees of the U.S. Senate were chaired by hardened segregationists. James O. Eastland, Democrat of Mississippi, chaired the Senate Judiciary Committee, perhaps the most important committee in the senate.

A majority on the U.S. Supreme Court, in the 1950’s and 1960’s, was progressive, but the court could only handle a limited number of cases.

The FBI back then was headed by J. Edgar Hoover, a racist who was fired up by black migration from the South and, later, the Civil Rights Movement, among other things. He had targeted Rev. Martin Luther King, Jack Odell, and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee.

What can one do when your ability to petition the government for a redress of grievances is systematically thwarted?

This was the legacy of the birth and development of the land of the free and the home of the brave. Or, as someone wrote, the land of the tree and the home of the grave.

Now let’s turn to the resistance to this system of degradation, to the legacy of the Civil Rights Movement. There have been movements for civil rights ever since there have been commissions of civil wrongs, whether at the Battle of Thermopylae in 480 B.C. or throughout history.

In 1960 four African American college students sat down at a whites-only lunch counter in Greensboro NC to simply get something to eat. They were refused service.

The students returned, in larger numbers, day after day. After five months the students were victorious. Meanwhile news of their courageous act spread like wildfire.

Soon there were sit-ins in 55 cities in 13 states. The Civil Rights Movement was gaining momentum.

A verse from a folk song back then tells us: “Here’s to the land you’ve torn out the heart of. / Mississippi find yourself another country to be part of”. But the truth is that racism had permeated the entire country, a part of the development, maturation and fabric of capitalism.

This maturation of the fightback was nurtured by reading and by struggle—concrete experience. When Malcolm X talked about the “blue-eyed devils” he was scorned but tolerated by the powers-that-be. Then he made his haj to Mecca and saw many “blue-eyed devils” in prayer. He returned to the U.S. with a new perspective. And so he had to be eliminated. And so he was eliminated.

When Martin Luther King fought for the right of African Americans to sit at the lunch counter with whites—he was tolerated, even uplifted, by the ruling class. Then he opposed the war we were waging against the Vietnamese people, as did SNCC, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee.

The saber-rattlers took notice. But way before that, in 1952, he had written a letter to Coretta Scott, later to become Mrs. King: I am much more socialistic than capitalistic in my economic theory.

In his last political act, King supported a strike by garbage workers in Memphis TN. He was linking the political dots, so he had to be eliminated. And so he was assassinated.

But I must go back even a few more years, to when I was a civil rights worker in Mississippi. In Mississippi, blacks generally, and black and white civil rights workers in particular, faced unbelievable danger: jailing, beatings, economic reprisals and, sometimes, death.

Vernon Dahmer, leader of the NAACP in Hattiesburg, Mississippi in the 1960’s, went on the radio to urge his people to register and vote, to not be afraid. He offered to pay their “poll tax,” if needed. A minister from the Delta Ministry of the National Council of Churches, Rev. Bob Beech, and I went to visit Mr. Dahmer. Mr. Dahmer gave us this sign, which had been affixed to a tree near his house.

The sign pictures, as you can see, a large Klansman in a white robe pointing at you with the slogan, "I want you in the White Knights of the Mississippi Ku Klux Klan."

It was the death threat of the KKK, I was told. Six months later Mr. Dahmer was dead. The Klan had hurled a firebomb into his home, burning him over 80 percent of his body. He died from smoke inhalation two days later. One of my daughters is named after him.

I was living in Columbia, Mississippi, thirty six miles away, when Mr. Dahmer was murdered. Two colleagues and I drove to Hattiesburg to pay our respects to the Dahmer family. We were stopped and closely questioned by the FBI, as if we were possibly the killers.

But the three of us had a pretty good alibi. We had just been released from jail in Columbia, having spent almost two weeks in the Marion County jail for protesting racist practices. So, we could not have murdered Vernon Dahmer.

Here are 2 examples of tampered mail. Yes, tampered mail. One envelope looks to have been crudely opened, the other seemingly steamed open. Both have the wording: Damaged in handling in the postal service.

Every movement since the Civil Rights Movement has learned organizing techniques from that movement. A proud legacy indeed. And there has been cross-fertilization, the connection between the United Farm Workers union and the Mississippi Freedom Labor Union. Then the UFW developed the boycott into a powerful instrument.

I heard that this helped the anti-apartheid movement in South Africa develop the boycott, and now the movement for Palestinian rights is developing the boycott further.

The Civil Rights Movement trained people for other movements. The anti-Vietnam war movement of the nineteen sixties was built by many people who had already been Civil Rights Movement veterans, as previously noted. There were also the support groups for southern actions, like Friends of SNCC, which led into the Berkeley Free Speech movement and then into anti-war actions.

The civil rights movement also trained us to recognize oppression and injustice when we saw it and to ask questions like "Who made that decision?"

With this legacy we learned to recognize how power is organized and how to hold specific individuals responsible. I am thinking of Jack Minnis of SNCC, whose "Care and Feeding of Power Structures" began this work--which is very useful in organizing things like boycotts.

We did not learn well enough, at that time, how to deal with vast moves in the capitalist economy which seemed then almost inevitable, like a law of nature. I, for example, did not understand neo-liberalism as it was beginning to develop.

Another example: the depopulation of the rural South and the destruction of rural communities and cultures was sort of taken for granted, even if we came to appreciate the beauty that these rural folk cultures had developed in spite of oppression. We assumed that these cultures would have to fit into a modernization process that they did not control. We helped them find a small amount more control than they would have had without the Civil Rights Movement--but not as much control as they should have had.

Vast amounts of knowledge that rural black southerners had about growing crops was simply allowed to vanish because we as mostly city people did not know what to do with it and assumed it would all become obsolete.

And the administration of Lyndon Johnson, regarded as among the most liberal of U.S. presidencies, was not about to challenge the control by planters of huge amounts of land.

We were so busy dealing with the Vietnam War that we had no time to deal with questions about agriculture and environment and community that seemed irrelevant at the time.

The legacy of the Civil Rights Movement in helping black southerners win political rights kept the mechanization of the plantations from being as destructive as it could have otherwise been. But the issues are important in other rural areas that face similar cultural destruction--for example, the Hispanic villagers of northern New Mexico.

And the destruction by corporate policies of white rural communities has been one of the factors that led to Donald Trump. We practically need a new Civil Rights movement to deal with what amounts to a nationwide Jim Clark (notorious Alabama sheriff) or Bull Connor (Public Safety Commissioner, Birmingham, Alabama)--without the competence of Clark or Connor, but that may well come with Trump's successors.

Fortunately, we have the experience of the Movement to draw on and I hope it will all be available in easy-to-research form.

I want to see that the records of the numerous legal troubles that we were involved in can in some way help Black Lives Matter, the Kentucky Alliance Against Racist and Political Repression, and other groups get more ideas for how to deal with the present struggles. But I bring up again--how do we help rural whites deal with the destructive policies of agricultural corporations like Monsanto?

Returning to the legacy of the Southern Civil Rights Movement. In 1965 nine hundred and fifty of us were arrested in one of the largest mass jailings of the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960’s.

I was in the first wave of those arrested. We were protesting the illegal convening of the Mississippi State Legislature, illegal because of the disfranchisement of its black citizens.

We arrived in prison trucks at the state fairgrounds, where cattle had been kept and then moved, and which were the same buildings where we would be housed. Women and men were separated, and I didn’t see my jailed sisters in the struggle until we were released on bond almost two weeks later.

After being booked, we had to pass through a cordon of Mississippi State Police. Some of us were beaten. In the cavernous hall where we wound up there were additional beatings--for protesting the cops segregating us, black civil rights protesters on one side facing whites on the other.

When “dinner” was to be served, the guards, as a form of control and humiliation, forced the whites to line up first. Each white inmate was given a slice of bologna stuck between two stale pieces of bread, and a paper cup with milk, or rather water with a little milk powder.

Each white guy returned with his meal to his spot on the cement floor on the “white” side, sat down cross-legged, and placed the cup on the floor, sandwich on top of the cup—in front of him.

Then the African American civil rights prisoners lined up to get sandwich and milk. They returned to their spots on the “colored” side, sat down cross-legged, placing cup on hard cement floor and sandwich atop.

No one ate. No one drank. After the last black prisoner took his seat, all of us prisoners, black and white together, and without pre-arrangement, picked up our sandwiches and broke bread as one. This is a legacy of the Civil Rights Movement.

I think often about the unabated courage of the movement's participants that was even more remarkable in the face of continuous fear. This alone is a profound legacy and speaks to the character and commitment on the part of those directly involved.

But undoubtedly for me the legacy centers around awareness and an awakening of the moral issues of segregation and race relations that the movement underscored. For the first time citizens began to understand the injustice and inhumanity toward blacks that the marchers and protesters demonstrated with their actions. I see a legacy left by the hundreds and thousands of individuals, many of whom are nameless, but contributed to the cause of justice. These are the unsung heroes.

And while so much remains to be done and the vigilance needs to remain constant, I think about how things would be today had The Southern Civil Rights Movement never developed. This was a point elaborated upon by the late Anne and Carl Braden.

The fight today against racism and economic privation, by Black Lives Matter, the Kentucky Alliance Against Racist & Political Repression and so many other organizations, reflects the continuity of sacrifice, even martyrdom, of the Civil Rights Movement: “They say that freedom is a constant struggle. We’ve struggled so long we must be free. We must be free.”

Let’s hope it can also reflect Karl Marx’s sentiment: “Labor in a white skin can never be free while labor in a black skin is branded.”

Power to the people!