'We were the United Auto Workers, and we felt like we were doing right.'

When the speed-up comes, just twiddle your thumbs

Sit Down! Sit Down!

When the boss won’t talk, don’t take a walk

Sit Down! Sit Down!

Sit down, just take a seat

Sit down, and rest your feet

Sit down, you’ve got ‘em beat

Sit down! Sit down!

-- “Sit Down” by Maurice Sugar

By BERRY CRAIG

AFT Local 1360

I’m thinking of Ermon Harp this Women’s History Month.

She left her native western Kentucky looking for work, not for a place in American labor history. Harp found both in Detroit, where she worked at the Advance Stamping Co. and joined one of the country’s first-sit down strikes.

The year was 1937.

“They called us Communists -- and just about everything else you could think of,” Harp told me. “But it didn't bother me a particle. We were the United Auto Workers, and we felt like we were doing right.”

She felt that way until she died at age 97 in 1992. To the end, independence and self-reliance characterized the union pioneer.

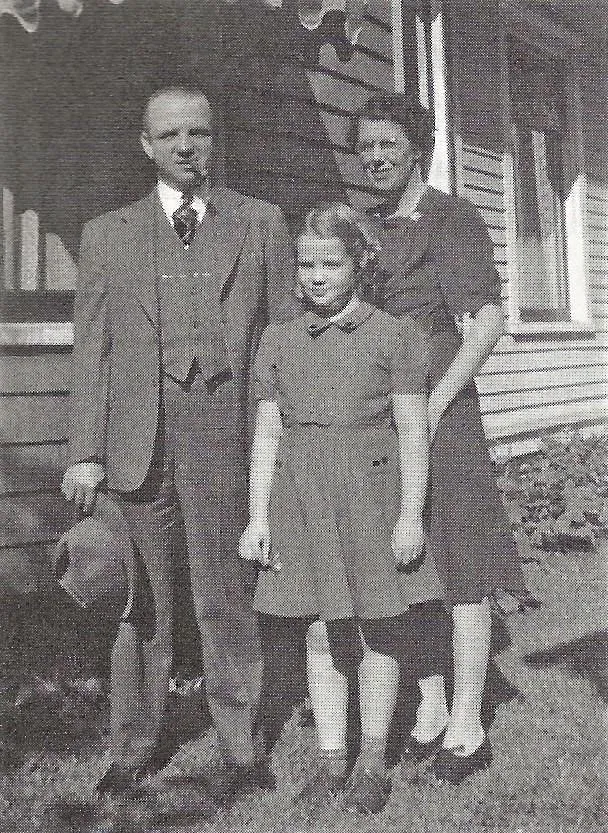

Ermon Harp and her husband, Lube, who was 75 when he died in 1970, were part of a mass migration of western Kentuckians to Detroit seeking work in the auto industry. Many auto workers returned after they retired.

Ermon, Lube and their daughter, Elaine, settled in Mayfield, the Graves County seat. The young couple had left Milburn, in adjacent Carlisle County, in 1922, after struggling to make ends meet on a hardscrabble farm.

Ermon and Lube weren’t the first Harps pressed to leave their hometown. While they aimed to escape poverty, other Harps had fled for their lives early in the Civil War. Pro-Union, they were driven out by armed Southern sympathizers from nearby communities who almost routinely raided Milburn, a tiny Unionist enclave in the Jackson Purchase, loyal Kentucky’s only pro-Confederate region.

Was Harp scared when she joined the strike? “Goodness, no,” she said. “There was nothing to be scared of.”

There was, of course. UAW organizers and members were fired, blacklisted and even assaulted.

The year Harp struck, Ford Motor Company guards severely beat union activists, including Walter Reuther, the UAW's president and guiding spirit for many years.

Historians credit the sit-down strike with helping pave the way for union organizing throughout American industry. The most significant sit-down strike began on December 30, 1936, at General Motors plants in Flint, Mich., near Detroit. In January, police stormed the plant. Workers repelled them and held on until February 11, 1937, when GM recognized the UAW.

The Flint-sit down “was the most pivotal strike in early UAW history,” according to the union. “It established the UAW as the sole bargaining representative for workers at the world's largest corporation and set the stage for organizing industrial workers across the United States.”

Harp’s strike came soon after the Flint sit-down. “I had no idea that what I was doing was making history,” she said.

Harp was among about 25 workers who sat down on March 1. A dozen were women, according to the Detroit Free Press. The paper reported that E.J. Nolan, the company president, said the strikers wanted “recognition of the U.A.W. as their bargaining agency, the rehiring of an employee discharged some time ago, and the abolition of the piece-work scale now in effect.”

Nolan said the strikers sought “a straight wage rate with an increase of approximately 35 percent.”

The paper explained that “the workers refused to leave the plant” when Nolan told them, “no negotiations could be made until the return of N.J. Nolan, secretary and treasurer of the company.” He also said “that workers coming to work in the afternoon were refused admittance.”

Advance Stamping employed about 170 people, all but 50 of them women, the paper said. The firm produced automotive and radio parts.

The strike was successful. On March 10, the U.A.W. announced that the company signed an agreement with the union recognizing the U.A.W. “as sole bargaining agency for 100 employees.”

Harp had a head full of memories about UAW organizing drives. “Our people were getting beat up all over town. But nobody got hurt where I worked. I guess it was because it was a small plant.”

When Harp sat down she was working on an assembly line, fitting together distributors for car engines.

The strike “went off smooth as you please,” she said. “There was no rough stuff."

“People brought us hot food, blankets and pillows. We organized a square dance. Some of the men played cards, and we turned the radio on to a church service on Sunday.”

Harp saw her spouse during the day, but the strikers stayed in the plant. “We found some big barrels, put some boards over them, spread down our blankets and slept pretty well,” she said.

At about the same time of Ermon's sit-down strike, Lube Harp joined the UAW at a General Motors factory where he worked. Harp said she became “union all the way” at the plant where she worked before landing a job at Advance Stamping.

“I'd worked there eleven years, when the boss came in one day and said, ‘Ermon, come pick up your check. You're through,'" Harp remembered. "Later, I found out he'd given my job to his girlfriend. That's why I went union and why Detroit went union. It was because of things like that that weren't fair.”

Ermon and Lube are buried side-by-side in Mayfield Memory Gardens.