Blair Mountain: ‘the largest armed uprising on American soil since the Civil War’

By BERRY CRAIG

AFT Local 1360

Most history books are silent about the battle of Blair Mountain, W.Va.

From late August to early September, 1921, 7,000 to 20,000 UMWA coal miners fought to shove 2,500 to 3,500 anti-union lawmen and volunteers off the mountain.

While the defenders were entrenched and had the edge in firepower, including machine guns and tear gas and pipe bomb-dropping airplanes, the advent of U.S. troops and Army warplanes forced the attacking miners to surrender.

The "10,000 armed miners set out to defy the government of the state and the companies that controlled their lives in the largest armed uprising on American soil since the Civil War," according to The Battle of Blair Mountain: The Story of America’s Largest Labor Uprising by journalist-historian Robert Shogan.

The big battlefields of the Civil War are national or state parks studded with monuments and memorials. Coal companies own Blair Mountain. After years of legal challenges, the battle site is back on the National Register of Historic Places and, thus, off limits to mining.

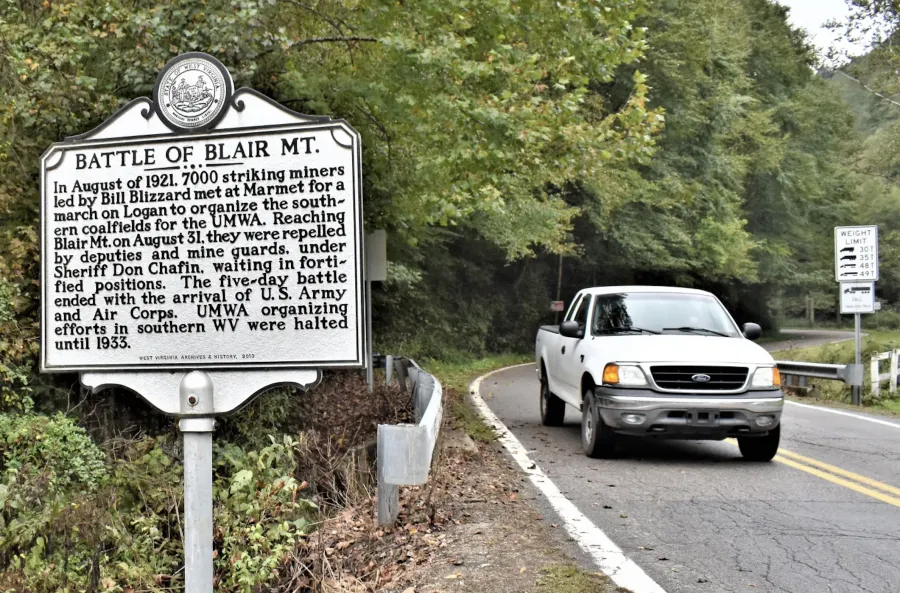

But nothing denotes the battle site except a state historical marker at the foot of the mountain in the tiny, unincorporated Blair community. (There was a big 2021 centennial observance that included a march along the route the miners took. Marchers included UMWA President Cecil Roberts.)

Next to W. Va. Highway 17, a two-lane blacktop heavily traveled by big coal trucks, the silver-painted sign explains that sheriff’s deputies and mine guards “waiting in fortified positions” held off 7,000 striking miners in a five-day fight. The miners' defeat halted UMWA organizing in southern West Virginia until 1933, the tablet also says.

Discrepancies over the size of the miner force reflect other conflicting details of the battle. Historians can't agree on how long the battle lasted or how many men were killed on both sides.

Despite the marker's claim of a five-day battle, fighting reportedly started as early as Aug. 25, peaked in the next few days and ended on Sept. 2 when federal forces arrived.

"While accurate figures are not available, sources estimate the number of miners who participated in the march at anywhere from 7,000 to 20,000," says the online West Virginia Encyclopedia.

Reportedly, the miners carried away their dead. "The precise death toll was never established, but estimates range from fewer than twenty to more than fifty," Shogan wrote. "Like other statistics in this event, the exact numbers of killed and wounded are mere conjecture," the Encyclopedia cautions.

In any event, the battle and Matewan are inextricably linked, according to labor historian Lou Martin. He's a professor at Chatham University in Pittsburgh and a member of the Mine Wars Museum Board of Directors.

“The Battle of Blair Mountain was in many ways the culmination of two decades of organizing and miners struggling for the right to unionize in the coal camps of southern West Virginia,” he said.

Much of that struggle centered on Matewan and its nearby mines.

The town’s West Virginia Mine Wars Museum is filled with rare relics, photos and displays that chronicle coal miners' early 20th-century efforts to unionize against union-despising coal mine owners. They fielded what amounted to private armies to defeat the UMWA.

Exhibits include a glass case containing spent cartridges, live bullets and the rusty remains of a Winchester lever-action rifle recovered from the Blair Mountain battlefield.

Other exhibits focus on the 1920 “Matewan Massacre,” the movie's climax and a precursor to the Blair Mountain battle, Martin said.

Absent a union, miners, including children, toiled deep underground in some of the deadliest workplaces in the country. Thousands were killed or maimed in cave-ins, explosions and other accidents. Black lung disease debilitated and shortened the lives of thousands more.

Coal company owners got rich by impoverishing miners, treating them like medieval serfs. Hours were long and pay skimpy. A miner, like "Sixteen Tons," the old Tennessee Ernie Ford song goes, owed his "soul to the company store."

"The company stores that sold them food and other necessities charged exorbitant prices, which the miners had to pay, since there was no other available outlet," Shogan explained in his book. "Just to guarantee the captivity of their consumers, coal companies paid the miners in scrip, which only the company store would accept. Even when wages rose, coal operators kept ahead of the game by boosting prices at the company store." (Scrip tokens are on display in the museum.)

Shogan also wrote that "miners worked in company mines with company tools and equipment, which they were required to lease, money that was promptly deducted from their pay."

Miners were paid based on the amount of coal they dug. Companies also cheated miners by paying them less than what they were owed, a scheme called "cribbing," according to Shogan.

Not surprisingly, miners flocked to join the UMWA and waged a series of strikes to force mine owners to accept unionization.

The owners stubbornly and violently resisted the union. They fired miners and turned them and their families out of company housing, which was rudimentary at best. (Rent also came out of a miner's pay.)

In addition, the owners employed strikebreakers and hired gunmen from the Baldwin-Felts Detective Agency to protect the scabs and to intimidate the strikers and their wives and children.

On May 19, 1920, a dozen Baldwin-Felts agents arrived by train from Bluefield, W.Va., to evict some local miner families, according to a state historical marker in Matewan.

Their mission accomplished, they headed to the depot to catch an afternoon train back to Bluefield.

Police chief Sid Hatfield (played by David Strathairn in the film) and Mayor Cabell Testerman (Josh Mostel) confronted the Baldwin-Felts men, who were armed with pistols.

Hatfield had a handgun and backup. Several miners, rifles at the ready, were hiding in nearby buildings.

Nobody knows who fired the first shot, but a gunfight erupted. Two miners, seven agents and the mayor died in a hail of bullets, four of which are still embedded in the back wall of a brick building.

Nineteen men, including Hatfield, were indicted and charged with murdering the Baldwin-Felts men. All were acquitted.

Meanwhile, anti-union Gov. Ephraim Morgan, a Republican, declared martial law in Mingo County. "The Matewan Massacre lit the fuse that became the Battle of Blair Mountain,” Martin said.

The pro-union Hatfield became an instant hero to the UMWA miners. Coal operators and Baldwin-Felts officers hated the lawman, none more so than Thomas Felts, the agency manager and co-owner. His brothers, Albert and Lee, were among the slain at Matewan.

Felts wanted Hatfield’s blood. He got it in Welch, the McDowell County seat, where the chief and his deputy, Ed Chambers, were put on trial in 1921 for allegedly blowing up a coal tipple.

“Many said it was an excuse to get them out of Mingo County so that Baldwin-Felts agents could kill him in retaliation,” Martin said.

Agents assassinated Hatfield and Chambers on the courthouse steps on Aug. 1.

Furious over the twin murders, UMWA miners began gathering at Marmet near Charleston, the state capital. Their leaders delivered a list of demands to Morgan. When he rejected the demands, they resolved to take up arms and march on Mingo County, which was still under martial law.

The miners planned to defeat the Baldwin-Felts men, break the power of the coal operators, free UMWA men jailed in Williamson, the county seat, and unionize county mines.

The marchers had to pass through Logan County, a center of union opposition.

Coal companies and Sheriff Don Chafin ran the county. Coal operators evidently boosted the pay of Chafin and his deputies for helping keep the UMWA out.

On Aug. 24, the miners headed toward Mingo County, about 84 miles southwest of Marmet. Their leader was UMWA officer Bill Blizzard.

"Many were veterans of World War I, and they organized themselves like an army division," the Encyclopedia explains. "The marchers had medical and supply units, posted guards when appropriate, and used passwords to weed out infiltrators. Marchers commandeered trains and other vehicles to take them to Logan County and confiscated supplies from company stores along the march."

When he heard the miners' army was on the way, Chafin, headquartered in Logan, the county seat, starting recruiting volunteers to bolster his deputies and the ever-present Baldwin-Felts men.

“Scores of Logan’s solid citizens responded,” Shogan also wrote. The sheriff described them as “lawyers, bankers, preachers, doctors and farmers.”

Chafin dubbed his army the “Logan Defenders” and augmented it with strikebreakers; those who refused to fight were fired, Shogan wrote. Help also arrived from elsewhere in West Virginia, including West Virginia State Police, members of the Welch American Legion Post and teenage Army ROTC cadets from Charleston High School.

With coal operators footing the bill, Chafin combed Logan for weapons, collecting machine guns and rifles. He also hired pilots and a trio of biplanes ostensibly to provide aerial reconnaissance.

Thus armed and equipped, Chafin led the Defenders to Blair Mountain's twin 1,800-foot peaks a dozen miles east of Logan. The sheriff knew the only route to Mingo County was over the steep-sided mountain.

The Defenders fortified Blair Mountain with breastworks, rifle-pits and trenches. They also blocked roads leading to top.

Chafin said he put about 2,500 men on the thickly forested mountain. He claimed he was told Blizzard had about 9,000 men under arms, Shogan wrote.

Though Chafin's force was clearly outnumbered, the sheriff had the upper hand. His men held the high ground, almost always a crucial advantage in warfare. Too, they were well dug-in and could outgun their attackers, who faced exhausting, steep climbs around rocky outcrops and through dense underbrush.

While some miners wore their army uniforms, others were dressed in civilian clothes. So they could tell friend from foe, Blizzard and his men tied bright red bandannas around their necks. The Defenders wore white armbands, according to Shogan.

“The bandannas became a symbol of the ‘redneck army,” Martin said. “It was also a symbol of solidarity. These were miners from many different backgrounds—white and black, native-born and immigrants. The red bandanna is still a powerful symbol today.”

When West Virginia's underpaid public school teachers struck earlier this year, many of them sported red bandannas. (The museum sells special Mine Wars Museum bandannas.)

As Blizzard's column advanced on Blair Mountain, the miners sang “We’ll hang Don Chafin to a sour apple tree” to the tune of “The Battle Hymn of the Republic,” Shogan wrote.

On Aug. 30, Republican President Warren G. Harding, pressed by a badly frightened Gov. Morgan, issued a proclamation threatening to send in the Army unless the miners dispersed by noon on Sept. 1.

When the miners refused to submit, Harding dispatched the soldiers.

On Sept. 1, Chafin's "air force" dropped pipe and tear gas bombs on concentration of miners. The ordnance exploded but inflicted no casualties, according to Shogun.

The troops didn't fire on the miners, and vice versa. After the soldiers arrived, Blizzard ended the fighting. About 1,000 miners surrendered to the Army; Blizzard and others fled, many of them abandoning their weapons on the mountain.

"Several hundred miners and their leaders were charged with various crimes from murder to treason," according to the Encyclopedia. "Most were given minor sentences, but serious attempts were made to punish...Blizzard...who was charged with treason. He was tried in Charles Town, Lewisburg, and Fayetteville before the charges were eventually dropped."

"The net result of the rebellion and the legal sequence was to inflict a devasting blow on the UMW in West Virginia," Shogan wrote. "The West Virginia local's treasury was drained as a result of the heavy spending to support the strike and wage the subsequent legal battles. Nor was there hope of help from national headquarters because the UMW landscape everywhere else was also gloomy."

In the Mountain State, union membership plummeted from 50,000 to a few hundred. Nationwide, UMWA membership slipped from about 600,000 to less than 100,000 by the decade's close, according to Shogan.

Anti-unionism was a big part of 1920s conservatism in business and government. Corporations pushed for the open shop, labeling the blatant union-busting scheme the "American Plan." Republican presidents and Congresses decidedly favored capital over labor, pushing tax breaks for large corporations and wealthy individuals, cutting regulations on business and blessing corporate America's anti-union crusade.

From 1920 to 1923 the American Federation of Labor, which included the UMWA, lost two million workers, or almost a quarter of its total membership. "And courts seemed to be ready to issue strikebreaking injunctions almost for the asking," Shogan wrote.

Martin agreed that the miners lost more than the Battle of Blair Mountain. "The coal companies broke the strike and were able to roll back union gains to a point where the United Mine Workers almost disappeared from West Virginia in the 1920s," he said. "The miners would go back to non-union mines."

He said the UMWA defeat in West Virginia "was also part of a series of worker losses in multiple industries after World War I."

Martin cited unsuccessful strikes in the steel and meat packing industries in 1919. "There was a massive assault on workers' rights to organize after the war and that also dovetailed with internal strife in the unions and a government crackdown on radicals [during the Great Red Scare of 1919-1920]."

While unions were down in the 20s, they weren't out. Unions dramatically rebounded in the 1930s under Democratic President Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal program for fighting the Depression.

Democratic Congresses passed the National Industrial Recovery Act of 1933, which a conservative Supreme Court declared unconstitutional. The subsequent Wagner Act (1935), gave workers legal protection to organize and bargain collectively. The NIRA bill and the Wagner Act triggered a tsunami of unionizing in mining and manufacturing.

UMWA President John L. Lewis put up signs in West Virginia and other coal states declaring, "The President wants you to join the union!" Miners flocked to the union with astonishing speed; 92 percent of the nation's miners packed UMWA cards within three months of the NIRA's passage.

"UMWA Local 1440 in Matewan is extremely supportive of the museum," said Martin.

A different kind of battle for Blair Mountain raged long after the guns fell silent. The opponents were people, including UMWA members, who wanted to preserve the battle site, and coal firms which owned it and aimed to extract coal via mountaintop removal, a process that would destroy the battlefield.

Mountaintop removal "is a form of surface mining in which coal companies clear-cut trees and blast away the mountain in layers from the top down, dumping rock and other waste byproducts into nearby valleys, until the site’s coal has been completely removed,' Rod Soodalter wrote in The Progressive.

At the same time, the second battle of Blair Mountain was hugely symbolic. One side wanted to protect a significant labor history site while the other wanted to obliterate it.

The Encyclopedia says that in 2006, the National Trust for Historic Preservation put Blair Mountain on the list of the nation's “Most Endangered Historic Places.” The National Park Service added Blair Mountain to its National Register of Historic Places in March 2009.

But the coal companies fought back in court. "Nine months later, however, the park service reversed its decision following a dispute about property ownership," according to the Encyclopedia. "Several groups—including the Sierra Club and the Friends of Blair Mountain—want the site protected from surface mining. They filed suit in an attempt to have the park service’s decision reversed. On June 27, 2018, the keeper of the National Register declared the removal erroneous and reinstated Blair Mountain’s listing."

Martin added that Local 1440 members, most of whom are retired, joined a peaceful march on Blair Mountain in 2011 to get the battle site restored to the National Register of Historic Places.