Workers accuse employers of pandemic safety lapses

Editor's Note: This article can only be accessed by Courier-Journal subsribers.

BY MATT MENCARINI

LOUISVILLE, Ky. — Through the heart of the COVID-19 pandemic, Kentucky workers lodged nearly 200 complaints against their employers with the state's occupational safety agency, accusing companies of dangerous safety lapses that raised the risk of illness and death from the virus.

A complaint from November 2020 said workers at the Kroger Distribution Center in Louisville were arriving sick with COVID-19 and managers weren't informing colleagues the virus was spreading.

Another from December 2020 pointed to 433 cases of COVID-19 among employees at Ford's Kentucky Truck Plant and said the Louisville company wasn't enforcing social distancing or other safety guidelines.

And a third from March 2021 connected an employee's death to COVID-19-related safety violations at Benchmark Family Services in Florence, describing "an overall lack of leadership."

These reported lapses, which the companies deny or dispute, were part of a spike in worker safety complaints that provide a window into COVID-19 dangers in the workplace and a cautionary tale as thousands of employees head back to their offices.

Overall, employees lodged 45% more complaints with the state's Occupational Health and Safety Program in 2020 than in 2019, according to the Kentucky Labor Cabinet. A cabinet spokesman said the pandemic may not have been the only factor driving the increase, since complaint volume can be cyclical.

Federal and state data compiled by the U.S. Occupational Safety and Health Administration showed 185 closed COVID-related complaints from Kentucky through May 21 — with only about 8% investigated.

As poor as that investigation rate is, it exceeds the national average. Across the U.S., complaint investigations decreased dramatically during the pandemic.

Critics for years have derided weak worker safety laws and enforcement, decrying dwindling budgets and staffs in worker safety agencies. The pandemic only exacerbated the problem, they say.

Debbie Berkowitz, program director of the National Employment Law Project's Worker Safety and Health program, said OSHA — and many states following the federal agency's lead — "totally abdicated its responsibility" to protect workers during the pandemic.

"They just failed to carry out their responsibilities," she said. "Thus, workers were left on their own. And because OSHA failed to respond to complaints, they failed to mitigate the spread of COVID-19 at work.

"And because of that, more workers got sick and more people died. I mean, OSHA's failure has enormous consequences here, and Kentucky OSHA was just following federal OSHA."

Still, Kentuckians kept seeking help for problems at their workplaces over the last 15 months, hoping for action.

Complaints changed as the pandemic progressed.

At first, many complaints reflected the national shortage of personal protective equipment. But more recent complaints frequently describedpoor management decisions and lax safety measures at factories, hospitals, medical offices and some of the state's largest employers.

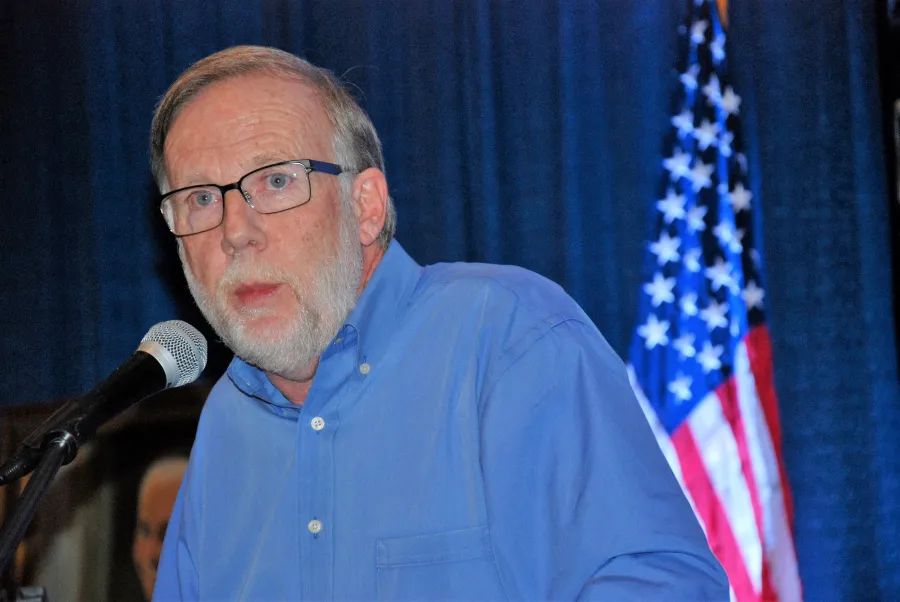

Bill Londrigan, president of the AFL-CIO of Kentucky, said some employers required social distancing, checked people's temperatures and provided masks early in the pandemic. "But many others didn't. So, you would expect people in those workplaces to complain about it and try to get some resolution."

COVID-19 now seems to be receding in Kentucky. As of June 15, 48% of Kentuckians had received at least one dose of the coronavirus vaccine.

Gov. Andy Beshear lifted the remaining mask mandates and other restrictions June 11, signaling the start of a return to normal.

But experts and worker advocates say there is still reason for caution given that millions remain unvaccinated and new variants of the virus may arise.

"There needs to be some sort of recognition that even though the rates of transmission and death from COVID have decreased due to the increase in the vaccination rates, that certainly it is not in the rearview mirror," Londrigan said."Protections should still be in place."

Many industries received complaints

Workers, who were not named in the data, filed complaints against 154 employers in Kentucky. Seventeen had a least two complaints. All complaints against private businesses in Kentucky were formal, meaning a current employee or representative submitted it in writing and it alleged imminent danger or a violation that could result in potential harm.

Major employers or large companies — such as Amazon, UPS, Ford and Walmart — accounted for 26 of the 185 total complaints.

There were 29 complaints against manufacturing companies, 24 against fast food establishments and restaurants, 12 against nursing homes and seven against car dealerships.

Nineteen complaints came from the health care field, with most in 2020.

They included instances such as one in May 2020, when an office worker at the University of Kentucky's Albert B. Chandler Hospital said there was no social distancing and requests to work from home were denied.

In another from November 2020, a Norton Healthcare employee said nurses and nurse assistants had to go into the rooms of COVID patients with only surgical masks and gowns instead of adequate personal protective equipment.

Kristi Willett, a spokeswoman for the UK hospital, said personal protective equipment was provided to all health care employees.

"While the nature of patient care and hospital operations doesn’t allow for the majority of employees to work remotely, positions were evaluated to determine those that could be done off-site," she said, adding that 93% of employees are now vaccinated.

Randy Hamilton, chief administrative officer of Norton Audubon Hospital, said in a statement the Norton complaint did not take into account U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidance or specific situations at the hospital.

"The safety of our employees is paramount," he said. "We provide our team members the highest level of personal protective equipment (PPE) needed based on the hazard."

About 30% of Kentucky's worker safety complaints were filed last fall. The Kentucky Truck Plant received two in late 2020, alleging a lack of safety protocols and more than 400 confirmed COVID cases.

Kelli Felker, a Ford spokeswoman, said the company worked with the union and infectious disease experts to develop safety standards.

"While we are aware of employees who have tested positive for COVID-19," she said, "no one identified as a close contact in the workplace who was following our protocols has developed symptoms or tested positive for the virus."

The complaints kept coming even after Kentucky's COVID cases peaked in January.

One concerning Benchmark Family Services, which provides therapeutic foster care, was lodged March 22 and listed numerous problems: "Death of employee due to ongoing COVID violations. Overall lack of leadership. Mandating employees be present in office despite rise in cases. Allowing employees to not wear masks. Firing of former regional director for working from home by day due to illness."

In an email, Sharon Scrivner, the state director Benchmark Family Services in Kentucky, called the allegations "blatantly false" and pointed out Benchmark is "an essential business," but she declined to comment on current or former employees.

"Benchmark Family Services follows the guidelines set forth by the state of Kentucky, including Healthy at Work requirements,"such as telework options, masks and social distancing, she said.

Masks a common issue

Many of the complaints lodged in 2021 suggested the national polarization around masks extended to the workplace.

One, filed against UPS supply chain services at the Cincinnati/Northern Kentucky International Airport, alleged most of the more than 50 workers refused to wear masks.

A subsequent complaint involving that airport, this one from a worker at the cargo business Worldwide Flight Services, said people were constantly coming in and out of the facility with no face coverings, despite a sign saying they were required.

A worker at Service Pros in Lexington, a flooring installation company, said in March no one was wearing masks and reported having pictures to prove it.

In the complaint against the Kroger Distribution Center in Louisville from November, a worker reported a lack of distancing and masks, along with concerns that others who had the virus were still coming into work.

Messages seeking comment from Worldwide Flight Services weren’t returned, and a Kroger spokesperson didn't answer a reporter's questions by press time.

Representatives for Service Pros, UPSand Amazon said their companies had safety measures in place, including masks and social distancing.

Complaint investigation rate low

Not all states have their own occupational safety agencies.

Kentucky has one of 22 comprehensive "state plans" approved and monitored by federal OSHA. Six other states and territories have state plans covering only state and local government workers, and the rest are covered by federal OSHA only.

A review of the federal and state data found that just 8.1% of COVID-related complaints in Kentucky — or 15 of the 185 — were investigated before being closed, including those against Benchmark and Norton, neither of which faced fines.

That compares with 5.2% of the 56,113 closed COVID-19 worker safety complaints nationally. (The data includes few details about open complaints and does not mention the state where they were filed.)

Compared with neighboring states — Indiana, Illinois, Missouri, Tennessee, Ohio, West Virginia and Virginia — Kentucky had the second-highest rate of inspections for closed complaints.

West Virginia's 16.3% was highest.

Nationally, a U.S. Department of Labor Office of Inspector General report from February said OSHA received 15% more complaints between Feb. 1, 2020, and Oct. 26, 2020, than during a similar period in 2019, but performed 50% fewer inspections.

And some were done remotely through phone calls, emails or letters.

Berkowitz, the National Employment Law Project expert who also worked as a senior policy adviser in OSHA during the Obama administration, said the agency and its state partners are too small for their assigned purpose, and were subject to political decisions made at the outset of the pandemic.

"The federal OSHA under Trump decided that they were not going to worry about our essential workers or frontline workers, who are mostly Black and brown workers, that they weren't going to impose requirements on employers and just hope they did the right thing," she said.

According to a 2020 report from the AFL-CIO, a national organization representing more than 50 labor unions, only nine employers were cited by the federal OSHA agency for not protecting employers from COVID as of Oct. 1, 2020.

At the federal level, the report said, OSHA had the lowest number since the early 1970s. It also noted that Kentucky has 26 workplace safety and health inspectors and 122,068 establishments that could be inspected.

A separate federal monitoring report examining Kentucky in the years leading up to the pandemic cited a low number of inspections. In their response, state officials attributed that partly to staff turnover and vacancies, which they didn't expect to improve in 2020.

State officials said recently they worked on several fronts to protect workers during the pandemic.

"Several state agencies, including the Kentucky Labor Cabinet, Public Protection Cabinet, and Cabinet for Health and Family Services worked to enforce the Governor’s executive orders to slow the spread of COVID-19 and protect Kentuckians in businesses throughout the commonwealth," Labor Cabinet spokesman Kevin Kinnaird said in an email.

Cabinet spokeswoman Holly Neal suggested the reason for the low percentage of inspections in the worker safety data compiled by the federal government may be because complaints pertaining solely to COVID-19 were transferred to a system called KYSAFER, a web portal and hotline that allowed the public to report businesses as well as organizations or gatherings that were not in compliance with Beshear's coronavirus-related executive orders.

Neal said KYSAFER investigations would not show up in the data compiled by the federal government. However, that database does, in fact, mention investigations into some worker safety complaints that were solely related to COVID-19.

And overall, the investigation rate for KYSAFER complaints was even lower than 8%.

State officials said KYSAFER received 54,897 reports through a web portal prior to Sept. 30, 2020, and 39,599 to a Labor Cabinet hotline. A total of 444, or less than 1%, of the 86,157 relevant reports, were investigated, but cabinet officials pointed out that the same entity could be the subject of multiple reports.

Return to office work on horizon

As COVID rates drop and more people return to workplaces, new challenges are arising.

Although customers might visit a business briefly, Londrigan said, workers are there for full shifts. And because it’s not always clear who has been vaccinated, he said some workplacesshouldn't abandon masks, even though "no one really likes it."

At the federal level, OSHA published guidance for reopening that recommends employers continue to consider remote work and keep stressing cleaning, disinfection, washing hands and social distancing.

Companies bringing workers back into the office will not only need to address physical safety, but also make sure workers feel comfortable being back, said Brad Shuck, a University of Louisville professor who focuses on organization and human resources development.

He created a four-step plan as a blueprint for how businesses should bring employees back to the office, stressing communication, planning andbeing nimble to change.

"Bad policy can really disengage good employees," he said. "Right now it's really important for organizations across industries to really think through: What are the policies that are important for us that we need to communicate? Also, what we may need to tweak moving forward?"

But to be effective, Shuck said those policies need to be enforced.

Thinking through the return-to-the-office plan and having masks, gloves or other safety items ready, he said, could help businesses avoid putting workers at risk and being on the receiving end of a worker safety complaint.

"The organizational culture ripple may last for years," Shuck said. "What we've experienced over the last 15 to 18 months will be something that defines the workplace of the future."